A Gay Jew in Paris in Search of Lost Time (& a New Identity)

After forty years of work-induced exile, I found I could no firmly longer grasp the idea of Paris as a city. Rather, its concreteness has taken on the mystical contours of a dream, which is understandable, seeing as I had dreamed about my return to the “City of Lights” at least once-a-month for decades.

My French Friend Kay, who is mixed race, African and Jewish, is teaching us about the history of Le Marais, with a deep history related to the Jews and also where gay people live and celebrate.

When I finally arrived, I felt lost. My visit would be short—a mere week—and I wanted to construct a kind of “container” that would help me ground and navigate my experience.

I called these containers “identities,” and they gave an organized structure to the various systems of the mind—the emotional, the physical, and the cognitive.

First, I had to establish my identity as a Francophile. I had the fundamentals in place: I could speak French at the Intermediate Level, and my accent was convincing enough to forgive any grammar mistakes. Luckily, one can finesse fluency in Paris by employing a cute, if meaningless, phrase. For example, to indicate you are about to ask a pertinent question, you might start your sentence with “Est-ce que?” and, if you were ordering something at a café, you could try “puis-je avoir?” without offending anyone. In this city, that “fake it til you make it” adage holds true!

Slightly more awkward, but necessary given my endeavors to launch my social media identity, “AskDrDoug,” I had to learn how to kindly ask a stranger to take my photo “Pourriez-vous prendre ma photo/notre photo?”

Parisians do appreciate when the “stupid American” knows his place and, rather than appear entitled, attempts to stumble through the mental cathedral that is learning a new language. They were patient with me whenever I asked, “parlez lentement, s’il vous plaît.” Can you speak slowly, please?

Doug and Kay

Kay is a dear “relation” to my former boss, Dr. Joy Turek, whose idea it was to start the LGBT Specialization in Clinical Psychology. Both of us consider ourselves to be “children” of Joy. To listen to Kay sing, check this out: https://youtu.be/1XZTaucrA10.

I also took for a spin an identity constructed through the magic of conscientious online dating: Doug, the well-meaning, gay adventurer whose intentions were clear: to taste a sample of delicious French pride and cuisine, if you catch my drift.

In the weeks before my trip, I had begun speaking with Franck, a French “bon mec” of Cameroonian origins. In Franglish, we intimated that me might become more inimate—thank the goddess for WhatsApp! If only I had the French equivalent of what the U.S. gays call “NSA…” Call me Mr. Big!

The French really do take a different approach to romance. I received a crash course in this fact almost immediately, with the first lesson being to use caution when walking into a patisserie if you are serious about sticking to that diet.

You should also be careful walking into a Parisian affair if you have any allergies or sensitivities to marriage. Thank the goddess again for the American family system’s invention of boundaries!

Franck worked during the day, and I was still doing tele-therapy with patients over Zoom, which left us just the evenings to have dinner together. Even with this limited engagement, more guideposts had to be established. Franck and I had to have a difficult conversation in a French African restaurant, one that caused us both some pain.

Leaning on the knowledge of Virginia Satir, the founder of the Growth-Vitality School of Family Therapy, I somehow found the words (in French!) to stress the importance of having realistic expectations for our time together. We should not dream of romance beyond our little tête à tête.

Luckily, the pain dissolved whatever glue being secreted by our traumatized inner children, and we were able to nurture a blossoming friendship. No one ever said a vacation should not involve hard work, nor that intimacy, in whatever idiom, would come sans les demons.

In this sticky situation, my therapist “identity” allowed me to use my words to set and reset boundaries in the most humane way I knew. Of course, even therapists make errors, for we are also patients of life and love.

Another “identity” always guiding me is that of being a Jew.

In Paris, I was lucky enough to meet up with Kay (that African Jewish woman and singer I mentioned in my last post), who immediately felt to me like a sister. Together, we walked through the Marais, a neighborhood not only where the Jews and Gays live and gather, but which is also a place of majestic history. Just outside the walls of Paris, in the northern part of the Marais, is the fortified church built by the Order of the Temple in 1240 A.D..

The Temple attracted other religious institutions to this district, which became known as the “Temple Quarter.” At the end of the 19th century, many Eastern European Jews were welcomed into the area around rue des Rosier. The Museum of Jewish Art and History, the largest French museum of Jewish art and history, can be found in this area.

Kay took me to the Place de la Bastille to see the "Génie de la Liberté" (the Spirit of Freedom), a gilded sculpture installed on a column to commemorate the revolutions of 1789 and 1830. It towers over the square which, at the time, was occupied by the Bastille Prison—a symbol of absolute power in the Ancien Régime ultimately stormed by the people.

As we took in history, Kay and I contemplated what it meant to be a Jewish person in the modern world. Both of us, we discovered, had constructed a separation around the “religious” part of our Jewishness despite having “observant” relatives—her mother and my grandparents, respectively. The God-Image was working for us anymore, though we both could appreciate the spirit of inquiry, social justice, humor, warmth, and irony tying us—two strangers—together.

We realized we shared the “identity” of a Jewish person who, despite a break with the religious aspects, managed to “keep the faith” through the quintessential search for knowledge and critique of accepted norms.

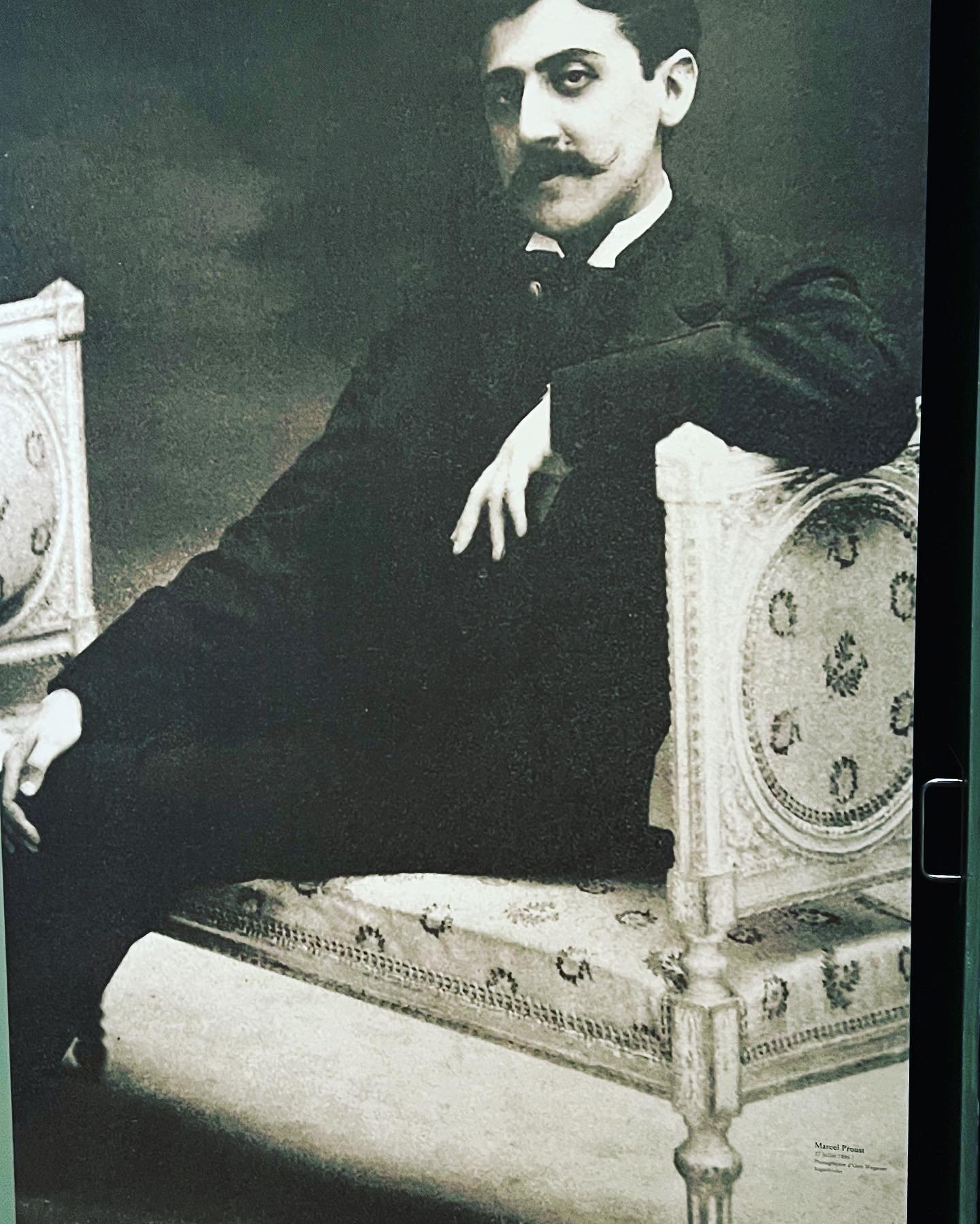

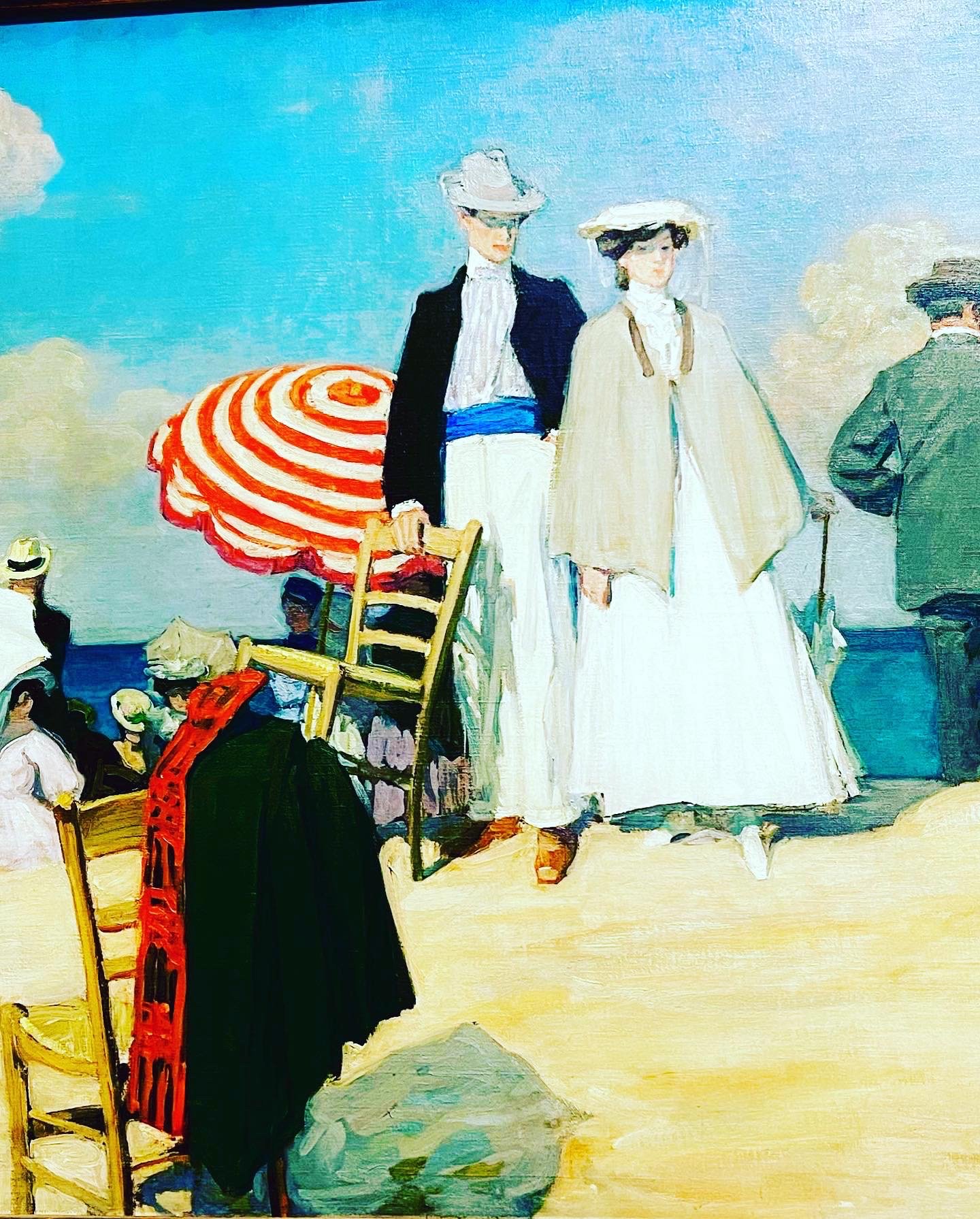

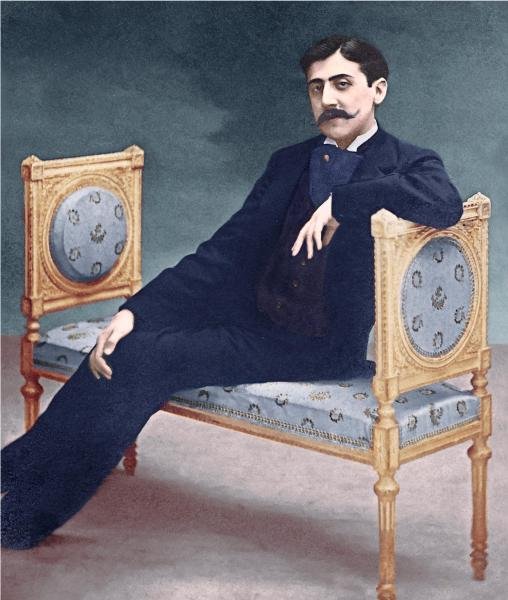

Owning my conversation with Kay, I visited the Museum of Jewish Art and History. It is located inside the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, and upon entering I was flabbergasted to discover there was an exhibit on Marcel Proust, a towering figure and personal hero.

Anyone who knows me as an “intellectual” knows how deeply indebted my heart is to Proust. It was one of my gay mentors, author Felice Picano, who first set me on this Prussian path. I also extend my gratitude to Edmund White, the author of several books on Proust who helped Felice create the first established group of mainstream gay writers, the 1970’s Violet Quill Group.

Dubbed “Marcel Proust: On His Mother’s Side,” this exhibit spoke to how Jewish heritage passes from generation to generation. Because Proust’s mother was Jewish, so, too, was he, making Proust not only a Jewish son, but also a masterful Jewish psychologist and, conceivably, a Jewish proto-founder of modern depth psychology and Gay Liberation. Mon Dieu!

Marking the centenary of Proust’s death, the museum had gathered 150 of his paintings, drawings, and documents to prove he wrote his seven-volume masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, to honor his mother after she died in 1905.

After highlighting the author’s ties with his mother’s family, the Weils (Jews perfectly integrated into the modern bourgeoisie of their time), the exhibit went on to illustrate Proust’s social life, the committed position he took regarding the Dreyfus Affair, his vision of the homosexual as an alter ego of the Jew, the burgeoning of modernism led by Jewish intellectuals and artists at the beginning of the 20th century, and the question of memory, a central element of Jewish identity and in the writing of In Search of Lost Time.

I hadn’t known of Proust’s interest in the Book of Esther and the Zohar—the Jewish characters in In Search of Lost Time—and was fascinated to learn of the similarities between the structure of Proustian manuscripts and that of the Talmud.

I spent my last Friday night in Paris tracking down a progressive synagogue friendly to queer Jews. Once inside the metal detectors of Beit Haverim (thanks to antisemitism, visiting any designated Jewish places is a high-risk activity), I was delighted to see a mixed congregation being led by a female Rabbi. A swishy male cantor was singing songs I recalled from my childhood, accompanied on the piano by an older French gentleman.

As one of two newcomers to the synagogue (the other was a Croatian woman), I was grabbed and shepherded to meet one of its leaders, a handsome, ardent young man wearing a Tallis. He loaded us gently with prayer books and prayer shawls, making sure we hadn’t lost our places.

The service was beautiful and, hungry for conversation once it was over, I turned to speak with the Croatian woman. Mina (I think that was her name) was soft-spoken but loudly brilliant—she had just received her Ph.D. in an elaborately complicated science. Hoping to find a home in the Jewish progressive tradition, I learned she was bisexual and in recovery from the abuse of her narcissistic mother’s doctrinaire Catholicism. Talk about an identity make-over!

Eager to extend our conversation, we found a bench in a nearby park. We talked for an hour, and I can honestly say she was one of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen: oval eyes, perfectly coiffed and curly hair, Parisian pastels, and a scarf. Toward Mina I felt a new but pleasant form of attraction—as a person.

Mina revealed she was in therapy, but her therapist, in an accusation of ambivalence, had discouraged her from going bi.

As happy I was to make this new friend a friend for life, I became fiery about what I considered to be the biphobia of her therapist. From that Parisian park bench, I gave an impromptu and impassioned speech on the generations-long fight of LGBTQ-Affirmative therapists against the “sickness model” of heterosexist therapy. I spoke of the domain of knowledge created to encourage treaters to “mind their own biases,” to never pathologize being queer, and to treat “bisexuality” as a rightful identity.

Mina, loving this brave heart, had dozens of questions to ask. She wanted to know more about therapy, being queer, and how the two were interrelated. Even though our conversation ended when Mina had to rush off to dinner (and likely, hot sex) with her new cute boyfriend, I could part knowing she would never return to therapy the same way again. Sadly, my phone died before I was able to take a photo of her.

After her departure, I felt suddenly lonely. I also felt a new kinship with the title of Proust’s masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, having felt the about-face of being alone and without means of communication after an hour of full of rich conversation and experience.

I walked home, asking passerby for directions to the major thoroughfare I knew would lead me back to my hotel. With only one day left on my itinerary, I felt overcome with big feelings of homesickness and loneliness. To gather my thoughts, I settled into a café. The gratitude I felt for the cute barman who let me borrow his iPhone charger was just a drop in comparison to the vast well of almost unbearable appreciation for my trip to Paris.

Ce bon mec a eu pitié de moi et m'a laissé emprunter son chargeur d'iphone. Il a travaillé au Café "Les Imposteurs", qui vient d'ouvrir près de la Place De La Bastille. J'ai vu des gens incroyables regarder et j'ai vu tous les hommes mignons s'embrasser sur la joue en se saluant et en se séparant.

All of my various identities had joined forces to guide me to the place I had unknowingly been evading—myself. More accurately, this trip reunited me with that part of myself that can feel simultaneously empty and full, the place known only to me, where great pain coexists with great pleasure, the secret source where the wholeness of one “identity” can finally be found. And I have only just made its acquaintance.

In this magical experience we call life, moments pass by so fleetingly and furiously that the second we try to grasp one with surety, it falls through our fingers. But grasp we must. So, too, must we embody, cry, breathe, ground, and wake-up—before the next moment catches us unawares.

I understand why psychotherapy is the only way to get going on this voyage of “lost time”—because of all the sciences, psychotherapy alone can honor the truth of change. Nothing remains the same; moment-by-moment our ideas and our databases are shifting, just placeholders guiding us toward deeper discovery on an eternal voyage still utterly human.

WTF?!

I will continue to puzzle over this conundrum of consciousness, and as I reach new understandings, I will share them with you.

In the meantime, read Proust. You won’t regret it.

À bientôt!